Your Majesties,

Esteemed Chairman and Members of the Norwegian Nobel Prize Committee,

The Honorable Prime Minister of Norway,

My Fellow Laureates, Chairman Arafat and the Foreign Minister of Israel Shimon Peres,

Distinguished Guests,

At an age when most youngsters are struggling to unravel the secrets of mathematics and the mysteries of the Bible; at an age when first love blooms; at the tender age of sixteen, I was handed a rifle so that I could defend myself.

That was not my dream. I wanted to be a water engineer. I studied in an agricultural school and I thought being a water engineer was an important profession in the parched Middle East. I still think so today. However, I was compelled to resort to the gun.

I served in the military for decades. Under my responsibility, young men and women who wanted to live, wanted to love, went to their deaths instead. They fell in the defense of our lives.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

In my current position, I have ample opportunity to fly over the State of Israel, and lately over other parts of the Middle East as well. The view from the plane is breathtaking; deep-blue seas and lakes, dark-green fields, dune-colored deserts, stone-gray mountains, and the entire countryside peppered with white-washed, red-roofed houses.

In my current position, I have ample opportunity to fly over the State of Israel, and lately over other parts of the Middle East as well. The view from the plane is breathtaking; deep-blue seas and lakes, dark-green fields, dune-colored deserts, stone-gray mountains, and the entire countryside peppered with white-washed, red-roofed houses.

And also cemeteries. Graves as far as the eye can see.

Hundreds of cemeteries in our part of the world, in the Middle East -- in our home in Israel, but also in Egypt, in Syria, Jordan, Lebanon. From the plane's window, from the thousands of feet above them, the countless tombstones are silent. But the sound of their outcry has carried from the Middle East throughout the world for decades.

Standing here today, I wish to salute our loved ones -- and past foes. I wish to salute all of them -- the fallen of all the countries in all the wars; the members of their families who bear the enduring burden of bereavement; the disabled whose scars will never heal. Tonight, I wish to pay tribute to each and every one of them, for this important prize is theirs.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I was a young man who has now grown fully in years. In Hebrew, we say, 'Na'ar hayiti, ve-gam zakanti' [I was a young man, who has grown fully in years]. And of all the memories I have stored up in my seventy-two years, what I shall remember most, to my last day, are the silences: The heavy silence of the moment after, and the terrifying silence of the moment before.

As a military man, as a commander, as a minister of defense, I ordered to carry out many military operations. And together with the joy of victory and the grief of bereavement, I shall always remember the moment just after taking such decisions: the hush as senior officers or cabinet ministers slowly rise from their seats; the sight of their receding backs; the sound of the closing door; and then the silence in which I remain alone.

That is the moment you grasp that as a result of the decision just made, people might go to their deaths. People from my nation, people from other nations. And they still don't know it.

At that hour, they are still laughing and weeping; still weaving plans and dreaming about love; still musing about planting a garden or building a house -- and they have no idea these are their last hours on earth. Which of them is fated to die? Whose picture will appear in the black frame in tomorrow's newspaper? Whose mother will soon be in mourning? Whose world will crumble under the weight of the loss?

As a former military man, I will also forever remember the silence of the moment before: the hush when the hands of the clock seem to be spinning forward, when time is running out and in another hour, another minute, the inferno will erupt.

In that moment of great tension just before the finger pulls the trigger, just before the fuse begins to burn; in the terrible quiet of the moment, there is still time to wonder, to wonder alone: Is it really imperative to act? Is there no other choice? No other way?

'God takes pity on kindergartners,' wrote the poet Yehudah Amichai, who is here with us this evening -- and I quote his:

'God takes pity on kindergartners,

Less so on the schoolchildren,

And will no longer pity their elders,

Leaving them to their own,

And sometimes they will have to crawl on all fours,

Through the burning sand,

To reach the casualty station,

Bleeding.'

For decades, God has not taken pity on the kindergartners in the Middle East, or the schoolchildren, or their elders. There has been no pity in the Middle East for generations.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I was a young man who has now grown fully in years. And of all the memories I have stored up in my seventy-two years, I now recall the hopes.

Our people have chosen us to give them life. Terrible as it is to say, their lives are in our hands. Tonight, their eyes are upon us and their hearts are asking: How is the power vested in these men and women being used? What will they decide? Into what kind of morning will we rise tomorrow? A day of peace? Of war? Of laughter? Of tears?

A child is born in an utterly undemocratic way. He cannot choose his father and mother. He

cannot pick his sex or color, his religion, nationality or homeland. Whether he is born in a manor or a manger, whether he lives under a despotic or democratic regime is not his choice. From the moment he comes, close-fisted, into the world, his fate -- to a large extent -- is decided by his nation's leaders. It is they who will decide whether he lives in comfort or in despair, in security or in fear. His fate is given to us to resolve -- to the governments of countries, democratic or otherwise.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Just as no two fingerprints are identical, so no two people are alike, and every country has its own laws and culture, traditions and leaders. But there is one universal message which can embrace the entire world, one precept which can be common to different regimes, to races which bear no resemblance, to cultures that are alien to each other.

It is a message which the Jewish people has carried for thousands of years, the message found in the Book of Books: 'Ve'nishmartem me'od l'nafshoteichem' -- 'Therefore take good heed of yourselves' -- or, in contemporary terms, the message of the sanctity of life.

The leaders of nations must provide their peoples with the conditions -- the infrastructure, if you will -- which enables them to enjoy life: freedom of speech and movement; food and shelter; and most important of all: life itself. A man cannot enjoy his rights if he is not alive. And so every country must protect and preserve the key element in its national ethos: the lives of its citizens.

Only to defend those lives, we can call upon our citizens to enlist in the army. And to defend the lives of our citizens serving in the army, we invest huge sums in planes and tanks, and other means. Yet despite it all, we fail to protect the lives of our citizens and soldiers. Military cemeteries in every corner of the world are silent testimony to the failure of national leaders to sanctify human life.

There is only one radical means for sanctifying human life. The one radical solution is a real peace.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

The profession of soldiering embraces a certain paradox. We take the best and the bravest of our young men into the army. We supply them with equipment which costs a virtual fortune. We rigorously train them for the day when they must do their duty -- and we expect them to do it well. Yet we fervently pray that that day will never come -- that the planes will never take off, the tanks will never move forward, the soldiers will never mount the attacks for which they have been trained so well.

We pray that it will never happen, because of the sanctity of life.

History as a whole, and modern history in particular, has known harrowing times when national leaders turned their citizens into cannon fodder in the name of wicked doctrines: vicious Fascism, terrible Nazism. Pictures of children marching to slaughter, photos of terrified women at the gates of the crematoria must loom before the eyes of every leader in our generation, and the generations to come. They must serve as a warning to all who wield power.

Almost all regimes which did not place the sanctity of life at the heart of their worldview, all those regimes have collapsed and are no more. You can see it for yourselves in our own time.

Yet this is not the whole picture. To preserve the sanctity of life, we must sometimes risk it. Sometimes there is no other way to defend our citizens than to fight for their lives, for their safety and freedom. This is the creed of every democratic state.

In the State of Israel, from which I come today; in the Israel Defense Forces, which I have had the privilege to serve, we have always viewed the sanctity of life as a supreme value. We have never gone to war unless a war was forced on us.

The history of the State of Israel, the annals of the Israel Defense Forces, are filled with thousands of stories of soldiers who sacrificed themselves -- who died while trying to save wounded comrades; who gave their lives to avoid causing harm to innocent people on their enemy's side.

In the coming days, a special commission of the Israel Defense Forces will finish drafting a Code of Conduct for our soldiers. The formulation regarding human life will read as follows, and I quote:

'

In recognition of its supreme importance, the soldier will preserve human life in every way possible and endanger himself, or others, only to the extent deemed necessary to fulfill this mission.

'The sanctity of life, in the point of view of the soldiers of the Israel Defense Forces, will find expression in all their actions.'

|

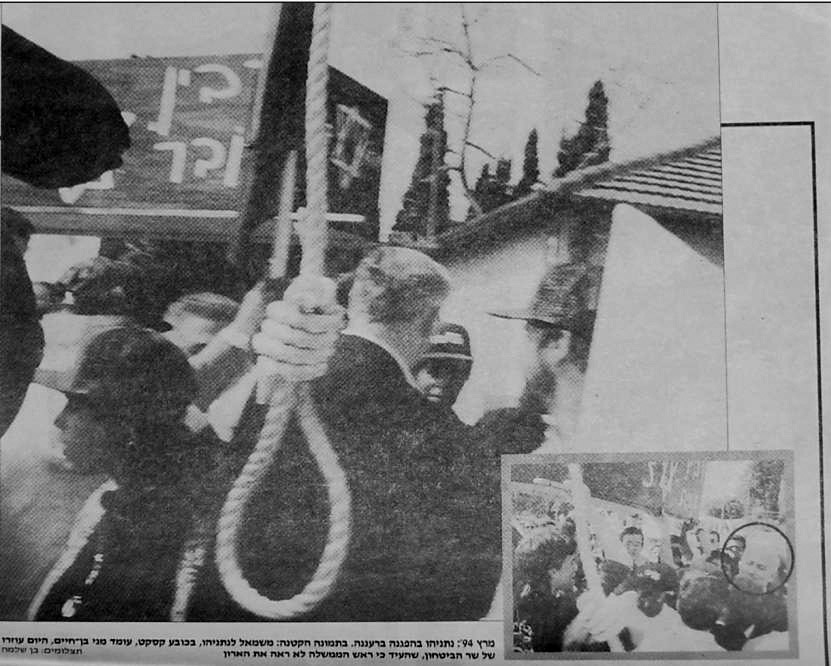

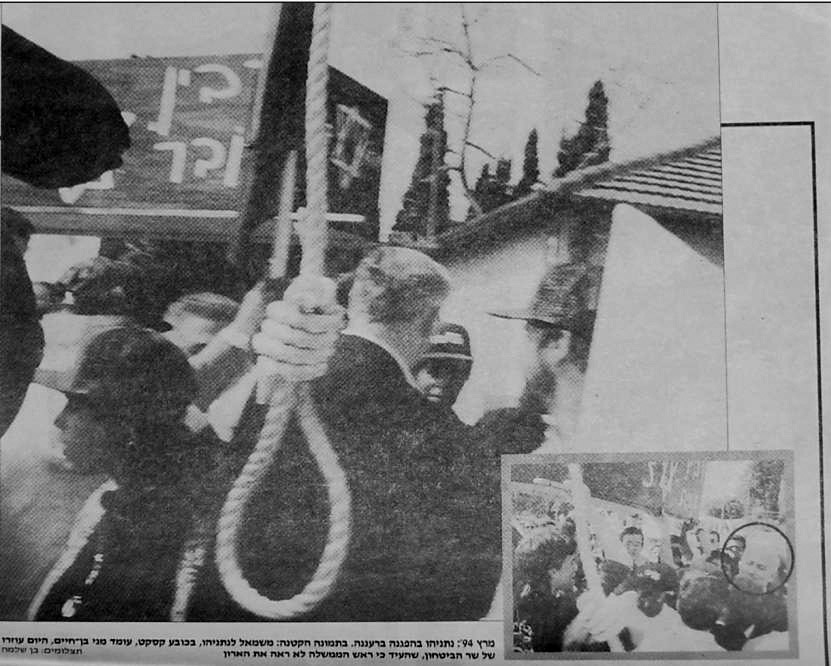

| Netanyahu protesting against Rabin with a coffin and hangman's rope |

For many years ahead -- even if wars come to an end, after peace comes to our land -- these words will remain a pillar of fire which goes before our camp, a guiding light for our people. And we take pride in that.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

We are in the midst of building the peace. The architects and the engineers of this enterprise are engaged in their work even as we gather here tonight, building the peace, layer by layer, brick by brick. The job is difficult, complex, trying. Mistakes could topple the whole structure and bring disaster down upon us.

And so we are determined to do the job well -- despite the toll of murderous terrorism, despite the fanatic and cruel enemies of peace.

We will pursue the course of peace with determination and fortitude. We will not let up. We will not give in. Peace will triumph over all its enemies, because the alternative is grimmer for us all. And we will prevail.

We will prevail because we regard the building of peace as a great blessing for us, for our children after us. We regard it as a blessing for our neighbors on all sides, and for our partners in this enterprise -- the United States, Russia, Norway -- which did so much to bring the agreement that was signed here, later on in Washington, later on in Cairo, that wrote a beginning of the solution to the longest and most difficult part of the Arab-Israeli conflict: the Palestinian-Israeli one. We thank others who have contributed to it, too.

We will prevail because we regard the building of peace as a great blessing for us, for our children after us. We regard it as a blessing for our neighbors on all sides, and for our partners in this enterprise -- the United States, Russia, Norway -- which did so much to bring the agreement that was signed here, later on in Washington, later on in Cairo, that wrote a beginning of the solution to the longest and most difficult part of the Arab-Israeli conflict: the Palestinian-Israeli one. We thank others who have contributed to it, too.

We wake up every morning, now, as different people. Peace is possible. We see the hope in our children's eyes. We see the light in our soldiers' faces, in the streets, in the buses, in the fields. We must not let them down. We will not let them down.

I stand here not alone today, on this small rostrum in Oslo. I am here to speak in the name of generations of Israelis and Jews, of the shepherds of Israel -- and you know that King David was a shepherd; he started to build Jerusalem about 3,000 years ago -- the herdsmen and dressers of sycamore trees, and as the Prophet Amos was; of the rebels against the establishment, as the Prophet Jeremiah was; and of men who went down to the sea, like the Prophet Jonah.

I am here to speak in the name of the poets and of those who dreamed of an end to war, like the Prophet Isaiah.

I am also here to speak in the names of sons of the Jewish people like Albert Einstein and Baruch Spinoza, like Maimonides, Sigmund Freud and Franz Kafka.

And I am the emissary of millions who perished in the Holocaust, among whom were surely many Einsteins and Freuds who were lost to us, and to humanity, in the flames of the crematoria.

I am here as the emissary of Jerusalem, at whose gates I fought in the days of siege; Jerusalem which has always been, and is today, the people, who pray toward Jerusalem three times a day.

And I am also the emissary of the children who drew their visions of peace; and of the immigrants from St. Petersburg and Addis Ababa.

I stand here mainly for the generations to come, so that we may all be deemed worthy of the medal which you have bestowed on me and my colleagues today.

I stand here as the emissary today -- if they will allow me -- of our neighbors who were our enemies. I stand here as the emissary of the soaring hopes of a people which has endured the worst that history has to offer and nevertheless made its mark -- not just on the chronicles of the Jewish people but on all mankind.

With me here are five million citizens of Israel -- Jews, Arabs, Druze and Circassians -- five million hearts beating for peace, and five million pairs of eyes which look at us with such great expectations for peace.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I wish to thank, first and foremost, those citizens of the State of Israel, of all the generations, of all the political persuasions, whose sacrifices and relentless struggle for peace bring us steadier closer to our goal.

I wish to thank our partners -- the Egyptians, the Jordanians, and the Palestinians, that are led by the Chairman of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, Mr. Yasser Arafat, with whom we share this Nobel Prize -- who have chosen the path of peace and are writing a new page in the annals of the Middle East.

I wish to thank the members of the Israeli government, but above all my partner the Foreign Minister, Mr. Shimon Peres, whose energy and devotion to the cause of peace are an example to us all.

I wish to thank my family that supported me all the long way that I have passed.

And, of course, I wish to thank the Chairman, the members of the Nobel Prize Committee and the courageous Norwegian people for bestowing this illustrious honor on my colleagues and myself.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Allow me to close by sharing with you a traditional Jewish blessing which has been recited by my people, in good times and bad ones, as a token of their deepest longing:

'The Lord will give strength to his people; the Lord will bless his people -- and all of us -- in peace.'

Thank you very much.

The assassination of Rabin

The song of peace - שיר לשלום

The end of Netanyahu's all too long, corrupt and destructive rule is coming closer. With mounting scandals and investigations, with several of his closest confidants being interrogated by the police and under arrest, Netanyahu does what he knows best - attacking others, primarily the opposition and the media, calling it a lynch against him.

He is the expert in carrying out lynch, and carries much of the guilt for the instigation that laid the ground work for the assassination of Prime Minster Rabin.

Netanyahu's rule shall not end the way he and others instigated against the true peace makers, but in shame, and in the renewal of hope and sanity.

|

| Now $9.99 in Kindle |

|

| $18 in English or Hebrew on Amazon |