After months of drought, with extreme weather and dry winds,

fires have been raging across Israel, beginning November 22, 2016.

More than ten thousand dunam have been burned in 200 fires,

with severe damage to forests, animals, villages and towns. A quarter of the

population in Haifa, the country’s third largest city, had to be evacuated, and

two thousand apartments and houses have been damaged or destroyed.

Human negligence lies behind the first fires, with the

extreme weather causing wide damage. Then, Palestinian arsonists, as it seems,

may have caused half of the fires, joined on social media by triumphant

encouragement, such as the imam of Kuwait's Grand Mosque, Sheikh Mishary Alfasy

Rashid, who tweeted “All the best to the fire.”

The tree is sacred, perhaps particularly so in a barren country

like Israel, where almost all trees have been planted. Since the beginning of

the nineteen hundreds, hundreds of millions of trees have turned the country

from swamplands into a land of parks and forests.

Those radical Palestinian arsonists (far from all

Palestinians) are committing crimes against humanity and against Nature, just

like those fanatic Israeli settlers (far from all settlers), who uproot

Palestinian olive trees.

Those radical Palestinian arsonists (far from all

Palestinians) are committing crimes against humanity and against Nature, just

like those fanatic Israeli settlers (far from all settlers), who uproot

Palestinian olive trees.

The fires are now being extinguished. Many are the local

heroes – fire fighters, voluntary guards at night, police and security forces,

people in kibbutzim and in towns, including many Arabs, who have offered their

homes for the many who have had to evacuate their own homes.

But an additional phenomenon during these times needs to be

mentioned, possibly opening a window to reconciliation, if the political

leaders will wisely choose that path:

Israel, recognized by the World Health Organization as the

world leader in emergency field hospital, sent to disaster areas around the

world, has this time had to ask for help.

Israel, recognized by the World Health Organization as the

world leader in emergency field hospital, sent to disaster areas around the

world, has this time had to ask for help.

The first to respond was – the Palestinian National

Authority, sending firefighters to help combatting the wildfires. And Egypt,

Jordan, Turkey, United States, France, Great Britain, Greece, Cyprus, Italy,

Croatia, and Russia are among the countries that have sent planes, equipment

and firefighters.

Israel has not been alone in this crisis. When it is over,

the Israeli political leadership will have an opportunity to change its

policies, to open a window to reconciliation, to invite the Palestinians (who

have been equally reluctant) and other neighboring countries, to begin a new

chapter, based on mutual recognition, mutual acceptance of responsibility, and

willingness to give to each other, rather than take.

Israel has not been alone in this crisis. When it is over,

the Israeli political leadership will have an opportunity to change its

policies, to open a window to reconciliation, to invite the Palestinians (who

have been equally reluctant) and other neighboring countries, to begin a new

chapter, based on mutual recognition, mutual acceptance of responsibility, and

willingness to give to each other, rather than take.

As a small gesture, 50% of royalties between November 27 and

December 31, 2016, from the two books of mine that pertain to psychological

perspectives on Israeli society (regardless of where you purchase them), will be donated to one or more organizations

devoted to promote peace and reconciliation, such as joint projects between

Israel and Palestine.

The Hero and His Shadow

“This is a fascinating book. … On the one hand, we see the

hero, the warrior, the pioneer, the fearless man of doing. On the other hand, we see the shadow, the

dark side, … You see this dichotomy between the internal feeling of strength

and forcefulness, and on the other hand a terrible fear.

In order to

properly understand Israeli society and the sometimes strange responses in

certain political circumstances, we need to understand this terrible fear that

is hidden within us.”

In order to

properly understand Israeli society and the sometimes strange responses in

certain political circumstances, we need to understand this terrible fear that

is hidden within us.”

Prof. Yoram Yovell, author and psychoanalyst.

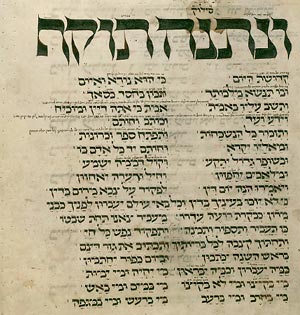

Requiem

"… Requiem is also a story of the alienation of the Western

intellectual Jew from their Jewish religious heritage and the potential for

finding a way back to a renewed Judaism and humanism through a new

understanding of self and other. … it is

a fight against denial, a battle for consciousness, and the courage to take a stand

against evil that define the integrity one can maintain even in a situation

that is seemingly hopeless in so many ways.

…"

Dr. Steve Zemmelman, Jungian Psychoanalyst

All my books are available at Amazon.