Leonard Cohen, Sept 21, 1934 - Nov 10, 2016

And who by fire, who by water,

Who in the sunshine, who in the night time,

Who by high ordeal, who by common trial,

Who in your merry merry month of may,

Who by very slow decay,

And who shall I say is calling?

And who in her lonely slip, who by barbiturate,

Who in these realms of love, who by something blunt,

And who by avalanche, who by powder,

Who for his greed, who for his hunger,

And who shall I say is calling?

And who by brave assent, who by accident,

Who in solitude, who in this mirror,

Who by his lady's command, who by his own hand,

Who in mortal chains, who in power,

And who shall I say is calling?

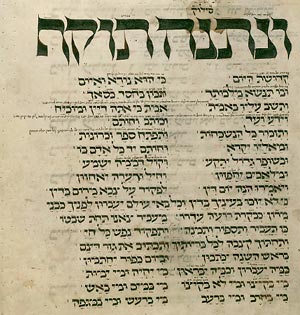

Who By Fire? is based on the prayer, U’netaneh Tokef, recited on the Jewish High Holy Days. Watch the song by Yair Rosenblum performed by Hanoch Albalak

U’netaneh Tokef:

"… On Rosh Hashanah will be inscribed and on Yom Kippur will

be sealed – how many will pass from the earth and how many will be created; who

will live and who will die; who will die at his predestined time and who before

his time; who by water and who by fire, who by sword and who by beast, who by

famine and who by thirst, who by upheaval and who by plague, who by strangling

and who by stoning. Who will rest and who will wander, who will live in harmony

and who will be harried, who will enjoy tranquility and who will suffer, who

will be impoverished and who will be enriched, who will be degraded and who

will be exalted. But Repentance, Prayer, and Charity annul the severity of the

Decree."

"For Your Name signifies Your praise: hard to anger and

easy to appease, for You do not wish the death of one deserving death, but that

he repent from his way and live. Until the day of his death You await him; if

he repents You will accept him immediately. It is true that You are their

Creator and You know their inclination, for they are flesh and blood. A man's

origin is from dust and his destiny is back to dust, at risk of his life he

earns his bread; he is likened to a broken shard, withering grass, a fading

flower, a passing shade, a dissipating cloud, a blowing wind, flying dust, and

a fleeting dream."

An excerpt from Requiem: A Tale of Exile and Return:

Abraham does not question his God, with whom he has sealed a covenant. He

binds his son Isaac and lays him upon the wood of the altar he has built. The

son submits to the father, Isaac to Abraham, and Abraham to God – a weakness of

character? Hardly, since Abraham has already proven his capacity to leave his

father’s house, and no less, when he argues and negotiates with God to spare

the sinners with the righteous in Sodom.

Perhaps Abraham did not ask any questions because this was simply his

adherence to the ancient practice of surrendering the first-born to the gods? The

Scriptures tell us Abraham offered up his “only son Isaac.” Consequently,

some Muslim scholars claim that not the little laughing one was to be

sacrificed, but Ishmael the first-born, who was the only one who could be the

only one of Abraham’s sons. Did not the God of compassion hear the lad who

cries of thirst, expelled from his father’s house into the desert?

“Is it not a common practice to this day for many a father to sacrifice

their sons on the altar of this or that divine expectation, of one or another

ideology or firm conviction?” Eli Shimeoni asked rhetorically, when suddenly he

started to tremble, as he wondered if this was what he was doing to his

children. Had he sacrificed them on the altar of his beliefs? Just to keep a

mad project going? Just because he thought, there was value in keeping an

ancient culture alive? Did not our national poet, Yehuda Amichai lament the

death of Stalin – mourning the leader of a country that recognized the State of

Israel, emperor of socialist equality, the victor over Nazism, rather than

celebrating the death of the dictator, murderer of millions? How easily do we

all fall prey to false believes, only in retrospect realizing how mad we were!

He wondered, if Abraham argued with Terah when he left his father’s house

and went forth to the land unto which God would lead him? What doubts pounded

in his heart when he put the burnt offering upon his son, for him to carry the

wood, some say cross, of his own sacrifice? Was this the wood of the sacred grove

that so meticulously had to be cut down, as when Yahweh commands, “build an

altar to your God upon the top of this rock, and offer a burnt sacrifice with

the wood of the Asherah which you shall cut down?” Without being asked, was

little Isaac to carry the Lord of Hosts’ mighty struggle against Asherah, the

goddess of the grove, on his shoulders? Was he to be sacrificed, bound to the

mother of the morning star and the king of the evening, the mother of the twin

brothers Shahar and Shalem – yes, Shalem, the Canaanite king-god and

mythological founder of Ir-Shalem?

The Biblical account is the skeleton of a drama, for the reader to flesh

out with feelings, and to be dressed in the garb of interpretations. There is

not a word of dialogue between father and son as they ascend the mountain of

worship – is it the awe of fate, the brevity of speech when walking straight

into inescapable tragedy, or is it the focused silence when you walk the line,

stretched to its limits across the cosmic abyss? Or maybe it is the chilling

coldness of mechanically executing daily movements, when you submit to

invincible catastrophe, as when rather than waiting for the five o’clock bus,

you are lining up at Umschlagplatz?

Is this the story of the Jews’ submission to the father, in which the

instincts of the sons bend to the fathers’ discipline, with the rabbis as a

Halakhic fortress cementing the power of God, the Father? Or is it the callous

need of fathers to castrate their sons, who on the one hand embody their future

and bring the prospect to “multiply exceedingly,” but who on the other hand, by

their very prime and youth, seem to hold the sword that separates the future

from the past, determining who by water and who by fire, who will rest and who

shall wander, as the poem recounts our disastrous fate on atonement day?

In some legends, he recalled, Satan tries to prevent Abraham from

carrying out the sacrifice. In his role as adversary, instigating toward

consciousness, Satan introduces some healthy doubt into what otherwise seems to

be passive submission. But in Biblical reality, it is only when the angel calls

upon Abraham not to slay his son, that he lowers his hand, and puts away the

knife with which he was ready to sacrifice his beloved son. He has passed God’s

test of devotion, and the ram is offered in place of Isaac.

But has he passed the human test of devotion?